Let’s keep to the theme of horticulture, shall we? And just to make it easy, we’ll choose a

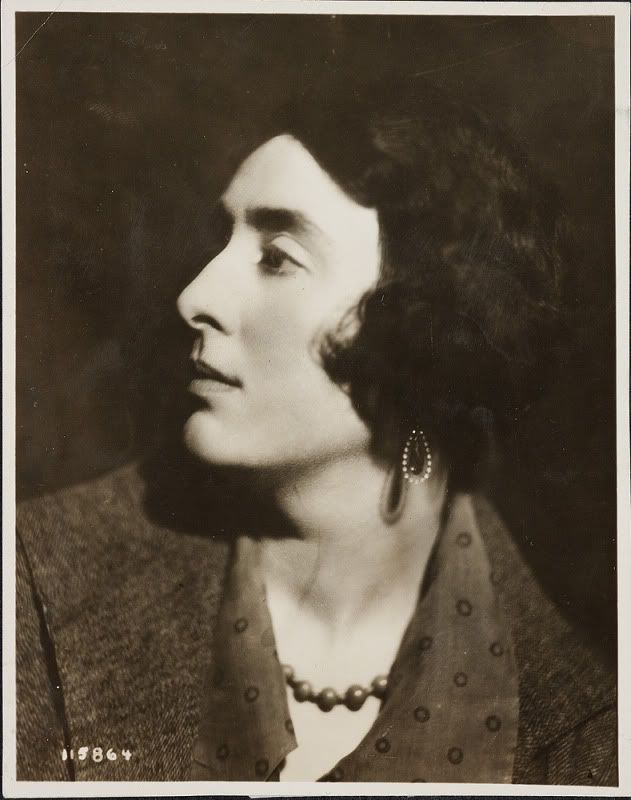

famous and flamboyant practitioner of the garden arts, Vita Sackville-West, creator of the

garden at Sissinghurst Castle in Kent. I doubt there’s a gardener alive who is ignorant of Vita’s

contribution to horticulture or hasn’t placed visiting Sissinghurst on their short list of must-see

gardens.

A noblewoman precluded by gender from inheriting her dynastic home Knole, a loss she suffered acutely from her

entire life. A diplomat’s wife, accompanying her husband, Harold Nicolson, on his assignments to Persia, where she

botanized and collected bulbs and hated playing the proper wife of a British civil servant.

A lover of women, most famously Virginia Woolf, who loved her in return but could not help but admit Vita wrote

with a “pen of brass.” Nonetheless, Virginia admired her fearlessness, the striding into drawing rooms of London’s

upper classes in jodpurs and pearls, and immortalized her friend in her own book Orlando, the account of a nobleman

yes, man, whose life improbably spans centuries and gender, just as Vita straddled the past and the present,

the crested and cloven, in mind if not body.

Mother of two sons (some contemporaries would suggest she was a rather indifferent mother to Nigel and Ben), she

first cut her gardening teeth at Long Barn before she and Harold bought the ruins of an Elizabethan manor house that was

Sissinghurst. It was here where they perfected their marriage of the formal and informal, where Harold laid out the severe

grid of box-lined beds which Vita filled to bursting with the perennials and old roses like ‘Celestial’ that she adored. It was

here that the white garden was envisioned in the winter of 1949, the “pale garden that I am now planting under the

first flakes of snow.”

Their own marriage also accommodated a rich interplay and complexity, affording the comforts of friendship, home, garden,

and family, his journalism, her poetry, but allowing each to pursue love affairs, in Harold’s case as in hers, with their own sex,

despite which their devotion to each other never wavered.

An award-winning poet (The Land). Recipient of the Veitch Memorial Medal from the Royal Horticultural Society.

Garden writer for the Observer, with a unique style wholly her own:

“The problem of the small garden. I received a letter which went straight to my heart,

more especially as it contained a plaintive cry that unintentionally scanned as a line of verse,

‘I never shall adapt my means to my desires.’ A perfectly good alexandrine, concisely expressing

the feeling of millions, if not of millionaires.”

And another favorite: “We All Have Walls…Often I hear people say, ‘How lucky you are to have

these old walls; you can grow anything against them,’ and then when I point out that every house

means at least four walls — north, south, east and west — they say, ‘I never thought of that.'”

(Surely the reader was bemoaning a lack of walls built with mellow 15th century brick, but

Vita’s advice is still practical, if a bit disingenuous.)

Vita died at age 70, in 1962, of stomach cancer, thought to have been brought on by the lead leaching from

the old cider press at Sissinghurst, leaving Harold bereft and utterly heartbroken. Sissinghurst was ultimately

handed over to the National Trust, despite Vita’s famously vowing to never have that shiny, hard plaque

affixed to her door.

Vita still speaks to gardeners of all means, even the castle-less, when she entreats us to “Follow my steps,

oh gardener, down these woods. Luxuriate in this, my startling jungle.”

a work of scholarly insight and detail — i salute you Ms. Ginger –i have searched the internet for this information and am glad to find it so well tended by you!