I’ve had a very interesting past couple of days. (Interesting in my usual narrow, horticultural sense of the word.)

Thursday I finally made it to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art to check out up close the new Eli Broad wing built by Renzo Piano and landscaped by artist Robert Irwin, conceived of principally as a palm garden.

But those are not the palms at LACMA, where I was Thursday. Rather, that is Licuala peltata in the Palmetum at the Rancho Soledad Nursery in

Rancho Santa Fe, California, about 90 miles south of Los Angeles, which I visited Friday. And where Robert Irwin chose the palms, bromeliads, and furcraeas for his gardens at the Getty Center and LACMA. In fact, he was there selecting more plants for both museums the day before my visit.

I’ll try to explain.

The whole week an unremitting theme kept bobbing up, no matter where I went, ever since the Garden Designers Roundtable posted on lawn replacement earlier in the week. For all the enthusiasm and knowledge of the GDR bloggers, I couldn’t help feeling that, for the Average Joe Homeowner, the ones living with the 40 million acres of lawn in the U.S., replacing lawn is going to be a tough nut to crack.*

And then Anne Raver’s excellent piece on lawn replacement in drought-stricken Austin, Texas, came out this week in the NYT, linked here.

From Ms. Raver’s article, quoting Mark Simmons, restoration ecologist:

“Instead of trying to persuade Americans to rip up their lawns and grow vegetables, Mr. Simmons is proposing a radically different kind of ground cover: a mix of seven native species, including buffalo grass, blue grama, Texas grama and curly mesquite.

Because each grass has different needs and habits, it fills a particular ecological niche, and the right matrix of plants keeps diseases from spreading and shuts out weeds, so pesticides are rarely necessary. Native grass also has roots that go down 30 feet, finding water when there is none to be had aboveground.

He isn’t content with just revolutionizing turf grass, though. He’s out to change our very perceptions of what makes an appealing landscape.

‘We have this expectation, left over from the Victorian era, that everything has to be green,’ Mr. Simmons said. ‘But we have savannas here, dark evergreen trees and grass like Africa that turns brown in the dry season. That’s the nature of plants.'”

Having just returned from a road trip up coastal California, enjoying miles and miles of tawny grassland studded with oak trees bearing dark green leafy canopies, I say amen, Mr. Simmons. I hope there are dozens more of you all across the country working on regional seed mixes for the drought-threatened acres of lawn in the U.S. Because as Susan Harris discusses in her post on Garden Rant linked above, there’s no easy solution, even for someone who lives and breathes the subject.

With all that churning in my brain, as I said I visited LACMA yesterday. And here’s what I found, some of which I admired and some I didn’t.

This I admire.

I knew Mr. Irwin had chosen lawn as the groundwork for his palm garden, and I fully expected to like it. Public spaces such as a museum are a wholly appropriate use of lawn. I expected a green plane out of which the statuesque, iconic palms would rise, the slender trunks never obstructive and always allowing for a generous view of Mr. Piano’s structure, with its floating red staircases made even more vivid against the green grass. And at first, from ground level, I saw how it all fit together and, though not overwhelmed, liked it well enough, especially the COR-TEN giant planter boxes and retaining wall. After Mr. Irwin’s flamboyant garden at the Getty Center, his restraint at LACMA was a complete surprise.

But before the afternoon was over, I grew to like it less and less, all that retro, gratuitous, and unnecessary green. I wanted a buff plane, maybe gravel or decomposed granite, out of which the palms would rise. In typically careless suburban fashion, many of the palms are planted directly in the lawn, with scrappy-looking watering basins at their base, like these triangle palms, Neodypsis decaryi.

Looking down from the second and third stories, I found the dirt basins unsightly when all else was crisp and clean lines. I imagined instead a geometric metal drainage ruff crafted to lay over the base of the palms creating a quiet rhythm when seen from overhead and hiding the watering basin. Also when viewed from above, the outline of the green fronds mostly disappeared against the green lawn. The view downward from those amazing stairways and terraces was frittered away.

Several times I mentally backed up when I reached a negative conclusion, trying to understand Mr. Irwin’s brief for the project, wondering if he was restricted in some way and required to use lawn in which to site these extremely drought-tolerant plants due to traffic flow issues. (There are weight-bearing and load issues, too, situated as the garden is over the parking garage.) Yet when a design causes one to muse over possible restrictions instead of manifest accomplishment, can it be called a success? The palms and lawn are growing in high raised beds bounded in COR-TEN steel, theoretically walkable, yet no one does. I asked a guard if I could walk on the grassy raised bed for better photos, and he said of course, so I jumped up. Within a few minutes a group of girls asked me if it was okay to walk on the raised bed. Other than our small group, I saw no one else leap the forbidding raised bed wall. Perhaps the walkable space is intended as overflow for special events?

It was all amazingly inert and static. The most plasticine of plants, furcraeas and bromeliads, were chosen, set in lawn, an anti-movement landscape, a conceptual reduction of a landscape.

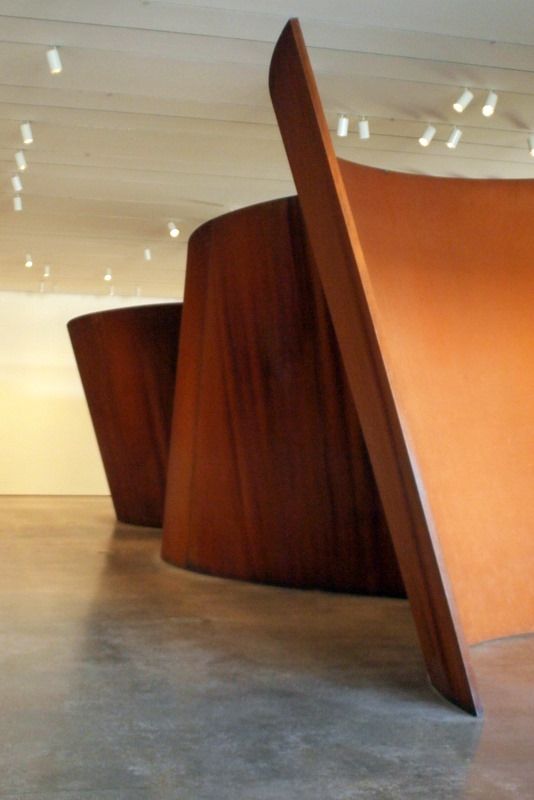

While inside the museum, sculpture was landscape. Richard Serra’s Band.

I also found perplexing that Irwin, an artist who famously approaches landscapes from a non-horticultural vantage point, would opt for a collection of palms, such a traditionalist horticultural approach, to landscape the museum wing housing one of the world’s most famous collections of modern art…okay. Never mind on that point. I get it. Let’s see. At the Getty Center, housing pre-20th century art, aided by the amazing plantsmanship of Jim Dugan, Irwin’s garden exploded in color, form, and movement, and was a sensual delight. Here at The Broad Contemporary Art Museum, I enjoyed looking at Irwin’s landscape about as much as any sensual enjoyment was to be derived from looking at the contemporary art collection it surrounded. Oh…

Oh! A contemporary, formal, almost denatured landscape to complement contemporary art.

(“How often have I said to you that when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.” Sherlock Holmes, The Sign of Four, Arthur Conan Doyle.)

Isn’t now a good time for some pure, unabashed plant porn?

A pseudo-palm, member of the Strelitziaceae/bird of paradise family, the giant Ravenala madagascariensis, taken at Rancho Soledad Nursery Friday.

As I said, the week had a theme. I’d been wanting to visit Rancho Soledad nursery for some time, home of the amazing aloe and agave hybridizer Kelly Griffin, whose initials were on so many of the succulent show plants I’d been viewing all summer. But close to a full day was needed to make the trip on a very heavily trafficked freeway. Friday came up with an empty calendar, so south towards San Diego we drove. Into 110 degree heat. Kelly Griffin was nowhere to be found, but I did learn that Messrs. Irwin and Dugan were shopping at the nursery the day before. I had no idea Rancho Soledad was the source for the LACMA plants but was told that any Furcraea foetida ‘Mediopicta’ I saw out and about came from Rancho Soledad.

Agave guiengola ‘Creme Brulee’

Agave potatorum, near some ‘Kichijokan’ but much more open.

I believe this is Agave parrasana.

A glimpse of the growing fields.

The nursery covers 25 acres, the heat simply staggered us, and the visit was cut way too short. As I waved goodbye, I vowed to return mid-winter with a broad-brimmed hat.

Other than some of the close-in photos and those taken in the Palmetum of Rancho Soledad, most of these photos are MB Maher’s.

*Last point on replacing lawn. I know my neighbors, their quest for order and tidiness, their busy schedules allowing only routine maintenance tasks at week’s end, which is exactly what a lawn asks of them. Safe, soothing, predictable. On my street there are no HOA restrictions on what to plant, no tricky grading or terracing issues, and the local water department has even been offering rebates to convert front lawns to drought-tolerant plantings, but still the status quo front lawn reigns supreme in my neighborhood. In last year’s drought, as good citizens, they let the lawn go crispy. But they are leaving the basic template intact of lawn on either side of a path to the front door. Because they are not horticulturalists/designers and would rather maintain than invent, and cannot visualize a replacement for the horizontal plane in front of their house, be it green or crispy, in rain or drought. Because neighborhood after neighborhood in arid Southern California contains tract homes that come equipped with obstinate spaces of varying sizes and shape for lawn to carpet. I wish they didn’t. I wish our tract homes sat on the land in an entirely different way. I wish underground cisterns for rainwater storage came with every home to catch all 15 inches of average annual rainfall. I wish the mostly useless space for front lawn was nonexistent, and instead the “hell strips” between house and street were huge, wide enough for a thin wood of trees to grow tall, unimpeded by roof lines and telephone wires, greenbelts buffering homes from the street, with generous paths for walking, bicycling, strolling at night, a sylvan Las Ramblas. I also wish there was no such thing as a driveway, that all car access happened in alleys and garages behind the house, out of sight. (If wishes were fishes, I’d be Jacques Cousteau.) In short, I think Average Joe Homeowner has the deck pretty solidly stacked against him. Sure, I removed the lawn when I moved into this house 22 years ago, but then I’ve got this growing obsession.

So much food for thought here Denise…

I enjoyed seeing the LACMA images as we visited back when many of these palms were still sitting in their shipping crates waiting to be placed. I don’t know that I would have picked up on the lawn disconnect right away but your photo of the palms from above certainly drives the point home.

You removed the 22 years ago? Truly ahead of your time, the neighbors must have been terrified about who/what had moved in. When we’ve been asked why we didn’t leave a little bit of our front lawn I always ask “why would we?” people seem to think it just would have been the right thing to do. I don’t get it. And while I do appreciate your point about lawns/grass naturally going golden in the dry months, and that’s great in wild open fields, I hate seeing it in our neighborhoods. Especially when it serves to showcase the weeds which stay green. How I would love to rip out every bit of sod on our street and plant alternatives…none of my neighbors “use” their front lawns, why keep them? What pleasure do they provide? I guess they do provide jobs, for the guys that pull up every week (or every other) in their trucks pulling trailers. They zoom around creating a cloud of dust and fumes (blowing grass and leaves from the neighbors into my gravel front garden) and pack up and take off for the next stop.

Loree, yes, I remember your trip to LA. It’s taken me this long to spend an afternoon at LACMA! As far as alarming my neighbors, I live on a fairly laissez faire street, but I did take the precaution to plant a box hedge along the front property line set back a few feet from the side walk, an evergreen presence for the neighborhood, and then went crazy with whatever I wanted to do behind the hedge. The box is now a privacy screen about 7 feet tall and amazingly drought tolerant, so it’s worked out OK. That’s funny about your ripping-out-neighborhood-lawn fantasy. I had a similar fantasy myself recently, involving asking permission to take over everyone’s hell strip, and get some unified vibe going down the street with succulents and bunch grasses. But I can’t even keep the weeds out of my own hell strip, much less take on the entire neighborhood’s!

Grass in places like that is so often strolling space for those big wealthy-donor galas that take place after the little people are shooed away for the day. I cannot think else why that damn lawn is there.

Will all the Furcraeas soon have weed-whacker scars? Unless LACMA has the best mow-blow guys in LA? As I seem to remember from skimming through the Getty garden book, (as well as seeing all those original azaleas out in full sun), Irwin doesn’t know anything about plants. How would a real plantsman/woman have done that space? Far better, I doubt not. Donors though need bragging rights. Irwin is a big name.

Hoov, I didn’t want to get into too much Irwin backstory — god knows this piece was long enough! — but I was, ahem, eavesdropping while exploring Rancho Soledad and heard a bit about Irwin’s visit the day before. I asked if he’s picked up more hort. knowledge after all these years. The sense I got was he has some, but that’s not what’s important for him. And the hort. knowledge is why he has Jim Dugan at his side. Going by birth dates, Irwin has got to be in his eighties by now. I can’t imagine how he fared in that 110 heat! I know I wilted.