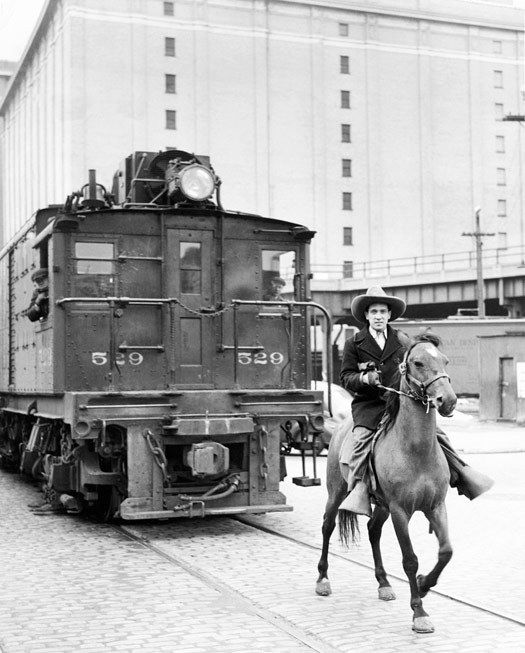

“Before it was constructed, the New York Central Railroad had operated a rail freight line at grade, or street level, along Tenth Avenue, and men on horseback (“West Side cowboys”) had ridden ahead of the train with red flags or lanterns to warn pedestrians of its coming; yet even with this picturesque alarm system, so many careless, inebriated or simply unlucky citizens had gotten run over that the street acquired the notorious name “Death Avenue.” For over 70 years, since the mid-19th century, public outcry had agitated against this danger to life and limb, demanding a safer solution: thus, the High Line.” (Here.)

Completed September 21, 2014, the High Line park has now become many things to many people, its Rashomon effect hashed out in the comments section of the many articles written about its success. It’s been five years since the first phase opened, with the third and final phase finished this fall. Over that span of time, my unadulterated delight at the railway’s rebirth into a park with plantings designed by Piet Oudolf has become complicated by learning of many other divergent reactions, and quite a few outright hostile ones, including accusing the park of being a Trojan Horse hiding rapacious developers. Because of the unimagined success of its new life as a beloved city park and tourist destination, drawing 5 million a year, it’s easy to forget its humble origins in community activism. I’ve seen neighborhood activism up close, and it isn’t always pretty. Contentious, divisive, disillusioning, these are what come to mind. Semi-contemporaneous with the grass-roots conversion of the disused railway line into a public park in NYC, my neighborhood association in Los Angeles was also involved in a grass roots effort concerning a property suffering from extreme landlord neglect, a property that slipped in and out of drug dealing. After years of frustrating engagement with the city at all levels, code, police, planning, the property seemed to magically accelerate on a fast track to a “pocket park,’ a cherished pipe dream of neighborhood activists. All of a sudden, the long-sought grant money was there, the city’s will was no longer wobbly but strong, and after years of dead-end efforts, the pocket park was a go. Plans were approved, the troubled property was sacrificed on the altar of eminent domain, and the park is now a year old. (I had nothing to do with the process, only attending a couple meetings and ceremonies.) The differences in scale between the two projects couldn’t be more stark, but I have to admit I had my doubts that either project would ever get off the ground. Another difference is that, unlike the High Line project, everyone in our neighborhood is wildly enthusiastic about our result. But then our neighborhood is in no danger of developers rushing in to build luxury penthouses to take advantage of views of our pocket park. (Some might say more’s the pity!)

The High Line experienced a similar acceleration when Giuliani and his pro-demolition sympathies left office, replaced by Michael Bloomberg, whose new agenda included finding innovative ways to include more parks despite the seemingly maxed-out density of NYC. The dream of a park in the sky found a powerful champion. With the completion of the final phase, and housebound with a sore throat, I dug a little deeper into the formation of the High Line, and what I found was a mulligan stew of community activism, timely rezoning, and a strange concept called “air rights,” mixed with insatiable appetites for high-end real estate development. The gentrifcation of this former manufacturing neighborhood was going to happen with or without the High Line. As with so many American cities, manufacturing had long decamped. Art galleries and designer ateliers had already moved in. Businesses directly under the disused structure were agitating for its removal to develop their valuable properties skyward. Ultimately, what came to the rescue of these disgruntled businesses as well as park proponents was ingenious manipulation of TDRs (Transferable Development Rights). And built into plans for the High Line’s redesign were considerations for unopposed views and open space that arguably wouldn’t have been a vision for this neighborhood’s growth had the High Line been demolished.

“High Line Adjacency Controls: Required Open Space

A minimum of 20% of the lot area would be required to be reserved as landscaped open space. To provide a visual extension of the High Line, the required open space would be located adjacent to and at a height not to exceed the level of the High Line. The required open space could not front on Tenth Avenue and could be used as a public or private space.” (Here.)

But back to the inception. The owners of the railway, CSX, who acquired it from Conrail in 1998, resisted the swelling outcry for demolition and opted instead to commission a study of potential uses. (Bless CSX for that.) Rail banking was a proposal that intrigued neighborhood residents Joshua David and Robert Hammond, both in attendance at that meeting unveiling the results of the study. (My community garden lies in a disused railway easement, and I wouldn’t be surprised if it’s also a beneficiary of rail banking.) After that momentous meeting, David and Hammond formed the nonprofit Friends of the High Line, fully in support of a park use for the railway.

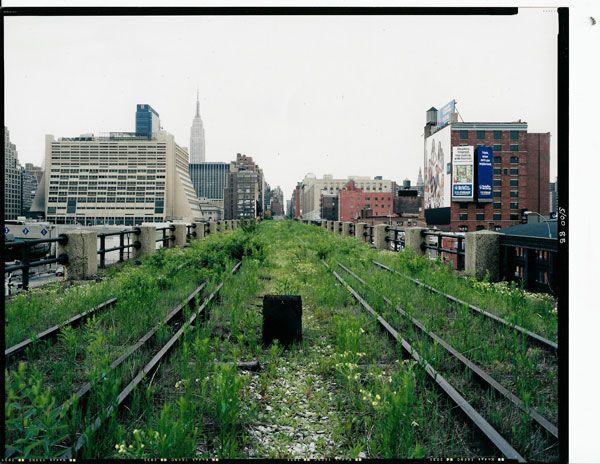

Along with requisitioning the potential use study, CSX fortuitously hired photographer Joel Sternfeld, whose evocative photos were just the boost the proposed park needed.

photo by Joel Sternfeld 2000

“One of the single most important things that happened to save the High Line in the very early days was when CSX made it possible for Joel Sternfeld’s project to photograph the High Line,” says David.

“They basically made it possible for the world to see what was on top of the High Line.” (Here.)

“In the beginning, we didn’t know what the High Line should ultimately look like. We didn’t know exactly what the design should be. We always thought the community and the city should decide what it should be. Over time, people coalesced around Joel’s photo and when you asked them, “What do you want the High Line to be?” they’d point to Joel’s photos and they’d say, “I want it to be like that.” In some ways, that was the biggest inspiration behind the design, Joel’s photos of the landscape.” (Interview with Robert Hammond Here.)

“Now when I see pictures of just the High Line without any people, I realize it wasn’t as good. It’s really beautiful when you have people interacting with the new landscape of the High Line.” — Robert Hammond Here.

What was striking is that in all my reading, not once was the amazingly complex plantsmanship of Piet Oudolf cited as part of the appeal that lures so many to the High Line. Through his plantings, Oudolf matched the spirit of Sternfeld’s photos of the abandoned railway recolonized by plants.

Where once there was a clang and clamor of industry, the noisy, physical manifestation of America’s 20th Century manufacturing might, the old railway has been repurposed for another kind of movement that seems to strike some as aimless, idle, purposeless: people making multivaried use of a park.

“The fact that this new amenity sprang from older industrial infrastructure says a lot about the current moment in New York’s evolution. A city that had once pioneered so many technological and urban planning solutions, that had dazzled the world with its public works, its skyscrapers, bridges, subways, water-delivery system, its Central Park, palatial train stations, libraries and museums, appears unable to undertake any innovative construction on a grand scale, and is now consigned to cannibalizing its past and retrofitting it to function as an image, a consumable spectacle. Productivity has given way to narcissism; or, to put it more charitably, work has yielded to leisure.” (Here.)

I would argue that instead of cannibalizing the past, the past has been honored and included in the present moment, which is a continuum that the wisest cities respect. I would argue that the High Line gives all of us, not just the 1 percent, million-dollar views of New York. And the fact that funding was found for a park (a park!) and not another sports arena still strikes me as extraordinary and reason enough to celebrate.

I’ve included photos of one of my visits to the High Line in June 2013.

“Railroad lines crisscrossing the country move freight, delivering everything from coal to cars. But one rail line running above the streets on Manhattan’s West Side moves your soul, delivering sanctuary amid coneflower and pink evening primrose.” (Here.)

Reading for this post can found at these links:

http://www.thehighline.org/

http://www.governing.com/topics/transportation-infrastructure/gov-nyc-mayor-bloombergs-urban-planning-legacy.html

http://journalism.nyu.edu/publishing/archives/portfolio/subramanian/HighLine_Resident.html

http://www.asla.org/ContentDetail.aspx?id=34419

http://www.hraadvisors.com/featured/the-high-line/#&panel1-4

http://www.preservationnation.org/magazine/2005/july-august/taking-the-high-line.html

http://www.mnn.com/lifestyle/responsible-living/sponsorvideo/improbable-journey-the-story-of-new-yorks-high-line

http://www.nyc.gov/html/dcp/html/westchelsea/westchelsea3b.shtml

Excellent reading Denise, thank you for compiling, editing, writing. I’ll get there someday!

So glad we have seen this amazing project. The best bit is that it has inspired other cities like London to do something similar.

This looks brilliant. It will be my first stop on any future trip to New York. Bucket list job.

Both projects have their dark sides–some few plutocrats in Manhattan making beaucoup bucks from real estate deals along the line, and the money for pocket parks magically appears because due to Megan’s Law, the more pocket parks you have the less sex offenders in your city. I am able to reject my cynicism at least somewhat through the thrill of the beauty of plants.

@Loree, you’re most welcome. Imagine something similar done with desert plants (I bet you easily can!)

@M&G, you guys really get around. Yes, Chicago has a project in the works too. I think Paris got there ahead of everybody, which I haven’t seen yet.

RD, it’s what finally got me to visit NY.

@Hoov, I’d be cynical too if the result was crap. There are those who enjoy life and those who enjoy deal making, and occasionally we have to cross paths.

I’ve enjoyed your photos of the High Line and hope to get there myself one day to take a tour. The controversy – and the fact that real estate investors will capitalize on the product – don’t surprise me. When I visited Tongva Park in Santa Monica, I noticed that a new, upscale condo development was going up right next door. And I’ve heard that developers in Woodland Hills in the San Fernando Valley, where I grew up and my brother now lives, have plans to create a green corridor in the area to improve its long-term business potential (Warner Center 2035 plan).

I am continually plotting my return to the High Line. Since seem to end up on the east coast once a year it is merely a matter of logistics. Logistics are no small matter in New York.

So enjoyable to have someone compile all these sources ofinformation on such an historic, ground-breaking project in one spot on your blog; thank-you Denise! These sorts of spaces remind me of how much I enjoyed wandering such abandoned sites in my youth, along with my yellow lab, being explorers of a past that no longer existed. In my case, it involved the yet-to-be subdivided vast landscaped grounds of the robber baron era in next door Hillsborough, with 100’s of acres in the hills and canyons that had at one time been planted out as vast botanical menageries, canyons damned to form lakes, secret abandoned gardens, abandoned estate homes and old roads crawling through wildlands which were slowly erasing their presence. All now developed with homes, 40 years later.I felt fortunate to be able to experience it almost to myself, and spent years exploring these estates.

I’ve yet to experience the Highline myself, but it resonates in the same way for me. Thanks for the insights and memories.

I’m going to NY this weekend specifically to visit the High Line! I can’t wait to see it. Your pictures and text have whetted my appetite.

@Kris, I need to get out to Santa Monica more often — I have a morbid fear of westside traffic!

@Kathy, it seems you are everywhere at once these days. Your frequent flier miles must be off the chart.

@David, there’s been such blowback on this project that I really wanted to dig around into its origins. Your childhood wanderings sound amazing. These are the kind of archaeological adventures available to city/suburban kids.

@Pam, so you’ll see the third phase. Excellent! Looking forward to your photos and impressions.

The High Line opened just a year or two after the last time I was in NYC and I so badly want to see it! Not sure when I’ll make it up there next but it’s at the top of my list of things to do!

While visiting Jim Golden’s garden just last week, I got cornered into a conversation with a couple from Long Island about the High Line. They just toured the new section and were complaining about the noise from railway cars that were still using some of the adjacent property. Seems the din made it impossible for them to enjoy the park. I wanted to say something like “what do you expect” or “didn’t you realize what this place once was”, or “you did know that you were in Manhattan”, but politeness got the better of me, and I offered that perhaps the still functioning nearby rails added to the charm. I am not sure they agreed.