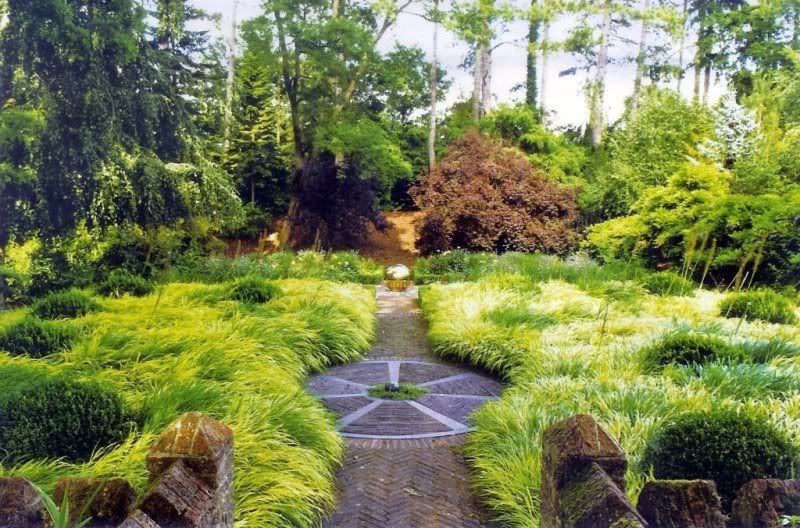

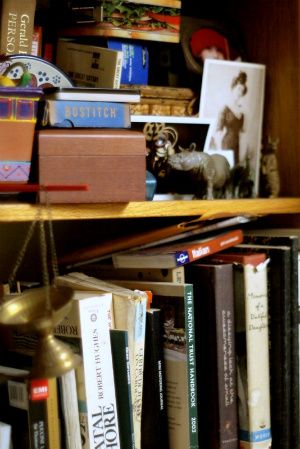

Hearing the news this week that Julian Barnes won this year’s Man Booker prize for his novel The Sense of an Ending had me searching for my unread copy of Barnes’ Arthur & George buried somewhere in a disgracefully cluttered bookshelf amidst rhinos, rabbits and a snapshot of Madame Ganna Walska. Also brought to mind was his short story, “Gardeners’ World,” from the collection Pulse, which presents a portrait of a marriage via the garden as battlefield, with gardening the banal pursuit of a couple whose relationship has gone a bit soggy. I’ve only read reviews and snippets of this mordant piece on a shared garden and haven’t yet bought the collection, since I freely admit that what little I’ve read of this story, although very funny, gives me the willies.

Hearing the news this week that Julian Barnes won this year’s Man Booker prize for his novel The Sense of an Ending had me searching for my unread copy of Barnes’ Arthur & George buried somewhere in a disgracefully cluttered bookshelf amidst rhinos, rabbits and a snapshot of Madame Ganna Walska. Also brought to mind was his short story, “Gardeners’ World,” from the collection Pulse, which presents a portrait of a marriage via the garden as battlefield, with gardening the banal pursuit of a couple whose relationship has gone a bit soggy. I’ve only read reviews and snippets of this mordant piece on a shared garden and haven’t yet bought the collection, since I freely admit that what little I’ve read of this story, although very funny, gives me the willies.

A brief exchange from the story:

“What have you done with the blackberry?”

“What blackberry?”

This made him more tense. Their garden was hardly that big.

“The one along the back wall.”

“Oh, that briar.”

“That briar was a blackberry with blackberries on it. I brought you two and personally fed them into your mouth.”

“I’m planning something along that wall. Maybe a Russian vine, but that’s a bit cowardly. I was thinking a clematis.”

“You dug up my blackberry.’

“Your blackberry?” She was always at her coolest when she knew, and knew that he knew, that she’d done something without consultation.

Other memorable lines include: “Can we please, please not call it a water feature?”

Only a British writer would be capable of producing such a withering, lacerating look at the territoriality issues in a relationship spilling over and turning gardening into a blood sport. If it seems like your cup of tea in fiction, more excerpts from “Gardeners’ World” can be found here.