UC Berkeley Botanical Garden’s symposium “Natural Discourse” held February 10, 2012, has been constantly in my thoughts this past week, whether riding the train, driving freeways, staring at the garden. I’d never visited UCBG before and found the physical location enthralling. I’ve been starved for rain, and a small rainstorm obligingly followed me up the coast, from Los Angeles to San Francisco, and rained off and on most of the weekend. For me, mist and rain always increases a place’s allure, and that day the canyon with its meandering creek and trails was magical.

Associate Director of Collections and Horticulture Chris Carmichael described this contemplated collaboration with artists as a new direction for this predominantly teaching-based botanical garden in an effort to broaden its appeal as part of an ongoing struggle to attract and connect with new visitors. This is an entirely new direction for UCBG, which dates its inception as a teaching adjunct to the university back to 1890. This “living museum” is a member of the Berkeley Natural History Museums Consortium and has only been open to the public since the 1960s. Bringing artists into this hallowed botanical garden to render site-specific works has not been accomplished without some gnashing of teeth by all involved, but like all of us, new survival strategies must be pursued in these tumultuous times, and botanical gardens are no exception. Despite the joking and joshing, deep affection and respect was readily apparent among all involved. A brief interlude to present Richard Turner with a Monkey Puzzle Tree, Auricaria araucana, in honor of his retirement from Pacific Horticulture, was a wickedly funny touch.

The UCBG houses one of the most diverse plant collections in the U.S., with its largest single collection that of cacti and succulents.

Only the Huntington Botanical Garden carries more species, though UCBG outstrips the Huntington in number of genera. Greater than 60 percent of UCBG’s collection is grown from plants collected in the wild. Scientists wishing to study a given plant can be assured that when they obtain specimens from UCBG, they will receive plants that derive from the exact genetic material of the plant as it existed in the wild. I’d love to include more of Mr. Carmichael’s talk on the mission of botanical gardens in general and UCBG’s in particular, but that will have to be saved for another post.

It was a revelatory day, but I find my notes were a bit too free-associative to be of much use in crafting a blog post, especially since many of the talks were deeply embedded in slideshows. All the speakers were uniformly excellent, but for this print format I think poet and garden writer Hazel White’s presentation might be a good place to start. Hazel drew from and read some of her new poems, “Peril As Architectural Enrichment” (Kelsey Press 2011), organizing her talk into a sonnet-shaped “14 lines of thought about liaisons between landscape and language.”

Hazel described a single moment in her “traditional” garden-writing career when a photo of a garden in a book rendered her speechless:

“Sixteen years ago I was writing only prose and what I consider now traditional garden writing for magazines. And then one day I was in my office looking at a landscape architecture magazine, turned the page, and there was an image that had an enormous physical effect on me. I had a sense of utter physical certainty and determination that I would do whatever I had to do to stand in that place. I don’t know quite how to explain it, but it was nothing to do with my thinking. It had absolutely a physical kind of jolting experience.”

The image was of the Carol Valentine garden in Montecito, California, designed by landscape architect Isabelle Greene, a garden which sadly no longer still exists in that form.

“So after seeing the image of the Valentine garden, this is the language I wanted to learn. I wanted to get at this interior emotion and replicate it for animation. So I went to the Valentine garden, and I did arrive there, and it was beautiful. Saxon has photographed it. It’s a white modernist home. It’s a white cube, and it’s on a steep hillside. And so in order to create an entrance court, the hillside had to be cut. So as you enter across a white bridge over a creek, you arrive in a gravel entrance court, and there are large white retaining walls on the left, and the house, which is a white cube, is on the right. And the surrounding landscape is of old oaks.”

Untangling that physical reaction to the Valentine garden led Hazel into an MFA writing program at California College of the Arts.

“Now, at that time I had been writing about landscape architecture for quite a while, and I figured I was very fluent in the language of gardens and that I could more or less read a garden. So I would know pretty quickly why it was working, and that’s what I would write about. But in this garden, I felt very physically alert and excited, and I couldn’t read it at all. Later Isabelle Greene told me that she leaves clues around to get people into the game. She’s an artist foremost. So this was not a question of garden design. This was not a question of focal points or establishing a sequence of entry or planting in threes and fives [laughter]. And I couldn’t write about it. I tried. And in many ways, I couldn’t get at the animation. So I identified I had a writing problem and I signed up for an MFA in a writing program. Very expensive way to view a problem.”

In attempting to “replicate animation” in the subsequent essay about the Valentine garden she would write at CCA, Hazel discovered she could no longer “maintain a linear, coherent, single focus,” and turned to a much-admired book written in the 1960s, “A Pattern Language,” by UC Berkeley’s Christopher Alexander, for clues. Alexander identifies five patterns of motion, “a syntax of human movement,” to which people are invariably drawn:

Shelter

“So that might be a window seat or, in the garden, it might be a bench against a hedge. It’s not a bench out in the middle of the lawn. Nobody sits in a bench in the middle of a lawn.”

Water

A view

“The bench against the hedge is going to be used more if it has a view from there.”

Play of light

“Now, that’s different from sunlight. So we’re not talking about uniform brightness at all, but actually the play of the light. So we are drawn to where light is happening. So, for example, we’re drawn to a bench where there’s light flickering through foliage in front of us. This is a way in which an umbrella over an outdoor table doesn’t work as well as a table under an oak.”

A sense of plenty

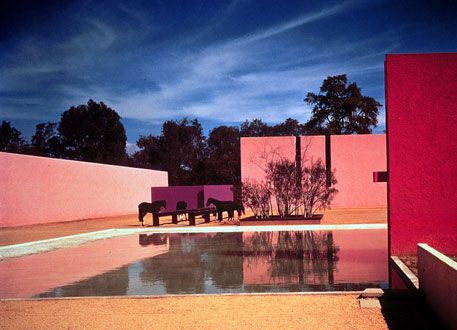

To describe how a “perfect garden” can be made from those five elements, Hazel chose a work by Luis Barragan in Cuadra San Cristobal, Mexico. (The next photos are examples of Barragan’s work, but I can’t be certain if they accurately depict the original garden in San Cristobal.)

Photo found here

“I have to talk about a special garden. It was made by the Mexican architect Luis Barragan, and it’s called the Plaza of the Horse Trough, and it’s a horse barn outside of Mexico City. It doesn’t exist anymore…So the requirement was a water trough for the horses. Imagine a trough 3 feet high, a concrete trough, and 5 feet wide and 50 feet long. This is a huge rectangle of water and it’s brimming. Water always has to brim in order to give a sense of plenty. There’s nothing worse than a pond that’s short of water. And so this horse trough, horse-drinking trough does brim, and it’s 50 feet long. And it sits in a plaza which is surrounded by old Eucalyptus trees maybe 100 feet high. And the wind in the foliage is casting shadows all along the horse trough. And as the sun comes through the foliage, it glitters and runs all the way up the horse trough. The horse trough is set in a plaza of soft, sandy, decomposed granite, a very fine surface, so the shadows from the tree and light play over that fine surface. There’s shelter also in the surrounding eucalyptus, but also there’s a fence. And then there are two walls, which are completely unnecessary, and this is a kind of example of how a fabricated element can add to the beauty of a scene. There’s a wall that’s white, and it looks about 30 feet high and 20 feet wide, and its only purpose is to be a screen on which the play of foliage is recorded. And there’s a blue wall, smaller, at the end of trough, bright blue, self-standing, and the view here is sky. And the water trough brings the view of the sky right down to our level. And the blue wall at the end of the trough is the sky...”

Photo found here

As with poetry, these five elements in a landscape compress meaning and bring an intensity of experience. Indeed, Hazel began her talk by reciting Seamus Heaney’s poem “Personal Helicon,” which represents her “linguistic and landscape heritage.” I know my own and many others’ physical impressions absorbed in childhood are the wellspring for feelings about landscape that “set the darkness echoing.”

Hazel’s sonnet that day, her 14 “lines of thought” for approaching landscape through language, began with Seamus Heaney’s poem:

1. Personal Helicon.

As a child, they could not keep me from wells

And old pumps with buckets and windlasses.

I loved the dark drop, the trapped sky, the smells

Of waterweed, fungus and dank moss.

One, in a brickyard, with a rotted board top.

I savoured the rich crash when a bucket

Plummeted down at the end of a rope.

So deep you saw no reflection in it.

A shallow one under a dry stone ditch

Fructified like any aquarium.

When you dragged out long roots from the soft mulch

A white face hovered over the bottom.

Others had echoes, gave back your own call

With a clean new music in it. And one

Was scaresome, for there, out of ferns and tall

Foxgloves, a rat slapped across my reflection.

Now, to pry into roots, to finger slime,

To stare, big-eyed Narcissus, into some spring

Is beneath all adult dignity. I rhyme

To see myself, to set the darkness echoing.

2. Replication.

“How one would know it was an experience of beauty rather than desire is if there’s an absolute urgency to replicate it…And then if it’s a big experience of beauty, a vow takes place. We stand there and we say we’ll never let another spring go by without standing here in this place.”

3. Arrival.

To “get us into the game” and “embody participation,” Hazel asked us to quickly jot down the “most beautiful landscape space” we’d ever been in and tell it to our seat mate. Mine was an abandoned field at the end of my childhood street, the only space in a suburban cul de sac that pulsed with nature in spring. Inundated and flooded by the winter rains, pollywogs spawned, and the grass grew lush and tall. In spring we carved out new paths every year, which dwindled and disappeared entirely in the drought of summer. Hazel was right. The mulberry tree was our shelter and provided a play of light, a view. A sense of plenty was everywhere in that little field. And risk, too, which Hazel singled out as adding an element of excitement to a space. My seat mate described ten summers on a Danish island, following the circuitous sandy pathways hemmed in by grasses to the water.

4. A new language

Hazel’s struggle to describe her reaction to the Valentine garden.

5. Patterns of motion

“How can a place make a body alert?”

6. A perfect garden

A space that can “call the eye and imagination into motion,” using the five elements from “A Pattern Language”; shelter, water, a view, play of light, a sense of plenty

7. Ethos of survival

Citing British geographer Jay Appleton’s habitat theory, “that our behaviors are dominated by what is survival advantageous,” critical to survival would be shelter and water, as is a clear view of predators. But wait.

“Those things all have to do with safety. We are intuitively driven also to take on danger. There’s a thrill to exploration, and to survive we actually need the greatest possible experience in differentiating between a shivering leaf in a tree and the movement of a predator. And there’s pleasure, physical pleasure, in exercising this process of differentiation.”

Describing the trail through the UCBG’s California Garden, “From here first you go across the creek, and you’re high above the creek, and the body is alert to the fact that you can actually slip and fall. And then you head down into the darkness. People will not usually head into darkness, especially downhill, so the path has to be clear and full of promise of light. So it goes down to darkness. It goes under trees, alongside bushes. And so I want you to notice the prepositions. Over, across, under, alongside. And so actually in landscape architecture and garden design, a path is made beautiful by introducing as many prepositions as possible. The body becomes alert to the difference between under and through and out and over. It’s a physical experience….And further on, there’s a set of steps that leads down to the creek, and steps give way to stepping stones in the creek. There are not many places where design allows you to take off your socks and get into the water. Up on the hill in the California Garden, there’s a place where there’s an enormous drop-off, and it’s wonderful that there’s no fence there…a frightening drop-off, and the path goes right to the edge. And if you fell, you would fall into the canopy of an enormous, old sycamore tree. In fact, it’s so deep you can’t see the bottom from the top. So it’s scary and it’s beautiful. There’s an enormous alertness in the body. So I’m making a case for risk. Although one might fall, risk can lead to maximal informational richness and physical pleasure, moving towards an aesthetics of inundation.”

8. A sense of plenty.

Brimming. Large and small, vertical and horizontal, solids and spaces, miniature and gigantic. Collections, orchards.

9. Revisiting beauty.

“If I’m not careful, if I try to replicate beauty, habit takes over. There are some forms of replication that don’t work, or they miss the mark, by which I mean they don’t gather momentum. For example, in Yosemite, people go into the shops in the Valley and buy mugs with Yosemite written on them. So our impulse to replicate can turn toward shopping.”

10. Impediments and tropes

“What is landscape? Speaking of it, I fall quickly into tropes. If I write about landscape, I feel I can’t write ‘fall’ without thinking or referencing the fall from Eden. I can’t write ‘seeds’ without the reader thinking rebirth. Light is transcendence. View is about eternity. Paradise is Hawaii. [laughter] Path is progress, and it’s always upward and positive. Darkness is racially laden and negative. Land is nationalism. Can I say frontier? I don’t think so. I can’t say mountaintop. Can I say valley? And most of all, dare I say beauty? People have stopped saying the word. It belongs to advertising and beauty salons.”

11. Reciprocity

“More and more aware of the reciprocal relationship between myself and the animate world around me.”

12. A clearing

“That threshold between shelter and view, clearing and woods, has a great deal of charge…There’s natural discourse and silence, one perspective and then another.”

13. Here Hazel read from her book of poems, “Peril as Architectural Enrichment”

14. (yours to fill in)

Unless otherwise noted, all photos by MB Maher.

What a heady bunch of things to think about- I don’t wonder that the day stayed with you. I’m enjoying thinking about gardens and spaces that I have had strong reactions too, and photos too. I realize that I am more apt to become attached to a photo;perhaps because I can return to it again and again without getting on a plane or starting up the car. I’m writing down these photos, and then I’ll find them. I would like to set them out on the table and look at them all at once. I wonder what that will tell me ?

Kathy, what the UCBG is doing is really exciting. It’ll be interesting to check in there. The “fog catchers” will be amazing. You must go there and report back in July!

The need to get this information out into a de-rarified sphere, to make it available for use, is the same need for replication that Hazel describes in her talk. To me, she is heir to the poet Anne Carson and peer to the phenomenologists who’ve been tinkering and inquiring into this body of knowledge since water first flowed thru Persian gardens.

MB, that did cross my mind writing this, blog as replication. AGO is waiting for your “perfect garden.”

Denise, What is amazing is that you have used your skills to record this for us. Talk about replication! This post is beautiful, thank you!

Regarding Hazel White’s reaction to the photograph of the Carol Valentine garden, “It had absolutely a physical kind of jolting experience”, I think she may have had a Brain Orgasm or Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response, ASMR. This phenomenon was first named in 2010. Hazel White’s experience seems to have taken her on a journey to understand and reproduce the feeling she got from viewing the garden.

I have had a similar experience twice. Both times it was viewing a conifer surrounded by winter-brown grass. I look for a similar scene constantly and relentlessly, hoping to recapture the euphoria I felt.