For summer, valerian and nicotiana light up what’s mainly a planting of shrubs and succulents the remaining seasons. As much as I love intoxicating displays of summer abundance, this little garden has to remain sober and on duty all 12 months of the year; otherwise, I’d be impossible to live with. Sadly true.

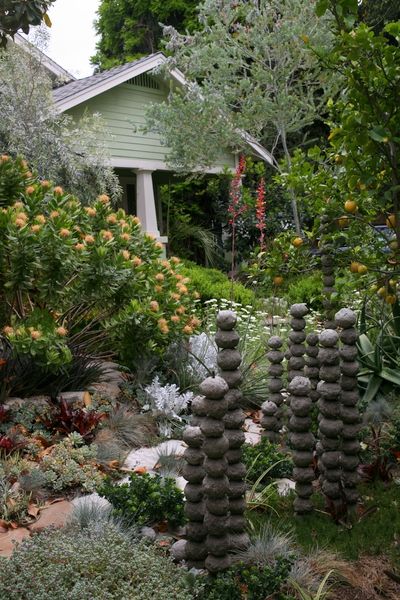

Summer does not make an overwhelming seasonal presence here in my little back garden but comes in quietly after the early poppies are over. Summer must make do, getting tucked in here and there, dotted throughout among the year-round plantings. And it’s not that I’m indifferent to a big summer display — if I had an acre in maybe a maritime zone 8, oh, about 30 inches of rain a year, I’d have a proper summer garden unto itself. What constitutes a summer garden is such a subjective state of mind anyway, isn’t it, dependent on climate, taste and temperament? For a zone 10 summer there’s lots of ways to go: serenely evergreen and austere; desert sculptural; chaparral shrubby; splashy subtropical, with curtains of vibrant bougainvillea and trumpet vines, or taking bits from each approach in varying combinations. I could happily go with desert sculptural and may get there eventually. And even though I find them loads of fun to plan, the big, complex, meadowy displays reliant on mature perennials, however, are the least likely to succeed. Most perennials give their best performance after three years, an age they never attain in warm winter climates without the requisite period of dormancy. Squeezed into the dry environs among agaves and aloes, my modest summery celebration for this year is going to look something like the following, which is very similar to past summers. Maybe some of the newly planted stuff like native buckwheats/eriogonums will surprise me and kick in later in the season.

I don’t need masses of blooms, but the shapes of flowers interest me as much as the shapes of leaves and the outline of the entire plant itself, such as how Cenolophium denudatum hoists its sublime floral architecture high above a fluffy, bright green base of parsley-like leaves (aka the Baltic Parsley).

Commanding attention along the same lines is Angelica stricta ‘Purpurea,’ taking it further with purple stems and leaves. I’ve yet to see any progeny from this biennial and have always had to bring in fresh plants.

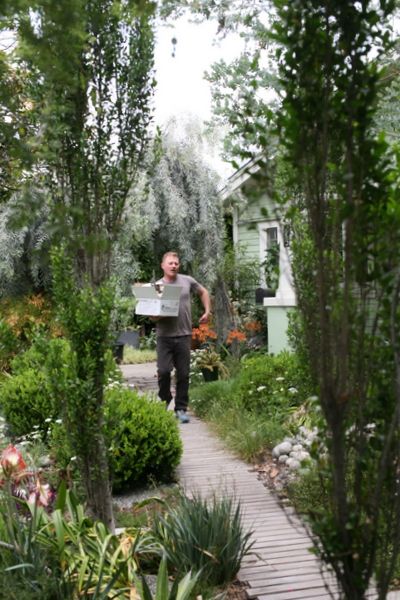

In zone 10 there’s an irresistible variety of evergreen shrubs and succulents to fill a garden, which means summer has to be light on its feet and find unobtrusive ways to make it work. Here the angelica is working it with bocconia, yucca and beschorneria, (with the angelica closest to the drip hose).

Cenolophium and the first blooms of Berkheya purpurea. If the cenolophium and Salvia ‘Waverly’ weren’t newly planted this year, they might be further along, but there’s a lot of summer ahead. And the salvias of course will outlast them all, blooming into fall.

Berkheya purpurea has expanded into three or four clumps now.

Giving the berkheya room to grow necessitates cutting back quite a bit on Leucadendron ‘Wilson’s Wonder’ and Senecio medley-woodii. The senecio is improved, becoming more dense and silvery the harder it is cut back, and who needs those raggedy yellow daisies anyway? The leucadendron cuttings go into vases.

Another senecio but new to me this year, CA native Senecio palmeri, is fighting for ground, pushing up around aloes. It’d be awesome to see this recently introduced senecio grown unimpeded into a big silvery dome. The yellow daisies are supposedly a positive feature on this one.

Out of a multitude of self-sown seedlings, the garden can comfortably fit only a couple wide-body castor bean plants, ‘New Zealand Purple.’ Furry, lance-shaped leaves in the foreground belong to CA native Lepechinia fragrans ‘El Tigre,’ also in its first year, with blooms like the South African foxglove ceratotheca but dangling sideways like an oregano. I hope it gets going before summer’s end.

And some heavily planted areas just have no room for any summer incidents at all. There’s no getting around it. Agaves take precedence! (Agave filifera ssp. schidigera ‘Shira ito no Ohi’)

Purple Awn Grass and Spanish poppies will sow themselves into the nearby bricks for summer, but I am determined to keep the walkways clear and have weeded out most of them, as well as some fine specimens of Verbena bonariensis which love such tight quarters.

The single carnations fit in nicely among the succulents. No need to stoop over to catch their scent either, it’s that strong.

Variegated Aloe arborescens will ultimately grow too large here but seems reassuringly slow growing for now.

And there’s plenty of heat coming from the ruddy coloring of Agave geminiflora, aloes, Cordyline ‘Red Planet’ and omni-blooming grevilleas. The arching sprays on the left are Puya laxa coming into bloom (which I just noticed coincidentally mimic the winter bloom sprays of the silver Kalanchoe bracteata).

And if Leucadendron ‘Jester’ continues to thrive, lookout cookout!

Aloe ‘Cynthia Giddy’ showing a flower bud and some seriously reddened leaves.

We’ve had near-constant overcast morning skies this spring, yet the succulents have achieved the most intense coloring.

In contrast, this photo from last July shows Aloe cameronii on the right almost completely green. Can’t wait for the grasses to return — maybe just slightly less exuberantly. Some of the growing agaves need the breathing room.

Similar view from February, with the grasses cut down, some of them moved further in the back near the acacia.

Pennisetum ‘Karley Rose’ is always the earliest. Jagged leaves belong to Eryngium pandanifolium.

Alstromeria ‘Third Harmonic’ is about 4 feet high now, planted at the canopy line of the purple-leaved acacia where some of the bigger grasses have also been moved. The recently planted flannel bush is nearby. Both of these vigorous plants have to contend with a lot of competition for resources, which should keep them in check but hopefully not kill them outright. And that’s the balancing act in a nutshell.

And since they’ve been photobombing nearly every image, I might as well talk up the irrepressible nicotianas.

They’re everywhere. Squeezed in between Leucadendron ‘Winter Red’ and Aloe cameronii.

For years nicotianas were a puzzle, and I assumed they were unsuited, maybe too delicate for zone 10. Once a few plants survived long enough to throw seed around, the hard part was over. After that it’s pure magic. Mine self-sow in white, lime, and brick red, the latter from Nancy Ondra’s seed strain. Now I can’t imagine summer without them. However, I still haven’t been able to crack the code of Nicotiana mutabilis yet.

The old standby, the bog sage, with Amicia zygomeris.

Solanum valerianum ‘Navidad Jalisco’ is in bloom again, romping through the Monterey cypresses on the eastern boundary.

‘

‘

Salvia curviflora is still managing to bloom as the shade under the tetrapanax increases.

I’ve been cutting back the Plectranthus argentatus to keep it upright but expect it to tumble earthward any day now.

So for summer, I guess this puts me in the desert sculptural, chaparral shrubby, splashy subtropical camps(?)

Maybe it’s more accurate to say I’m in the “whatever I can get away with” camp…