From a garden on the Los Angeles Garden Conservancy Open Days tour last weekend.

From a garden on the Los Angeles Garden Conservancy Open Days tour last weekend.

A garden I visited on Saturday decidedly belonged to a devotee of the variegated leaf. (It takes one to know one.)

The infatuation wasn’t apparent at first glance. This was a mature garden, well-treed, bambooed and shrubbed.

But after every twist and turn, in every shady nook, another splash, blotch or stripe of variegata lurked, awaiting discovery.

Variegation has multiple sources, and one of my favorite for wordplay purposes is chimeral; a plant composed of genetically different layers.

Fallopia japonica ‘Variegata,’ the Japanese Fleece Flower

Acanthus mollis ‘Tasmanian Angel’

variegated monstera, the Swiss Cheese Plant

variegated alocasia

Even a variegated pine, growing in a large container, Pinus wallichiana ‘Zebrina’

This is such a sweet agave for containers. Under a foot across in ultimate size, it is nevertheless a busy little mother. Just before its photo, I had cleaned out the offsets it produces so freely, which I’ll grow on to size in the front gravel garden. I did the same thing for Agave ‘Dragon Toes’ yesterday, another beautiful agave on the wee side. I wouldn’t mind at all having sweeps of these compact beauties. San Marcos Growers discusses provenance, nomenclature controversies, and hardiness on its site here. I don’t see this agave too often in nurseries, despite its propagation by tissue culture and all those pups it produces. When it finally made the local nursery circuit last year in a small (cheaper) size, I pounced.

It still surprises me that snails glide their delicate slipper foot over spiky, barb-leaved agaves, but they do, as seen in the damage caused to a few central leaves.

I’d recommend a smooth-sided container that easily releases the mother plant so those pups can be nabbed as soon as they appear.

edited 2015 to note that this agave is gaining acceptance under Agave applanata ‘Cream Spike.’

I’ve recently added the houseplant section to my itinerary when visiting plant nurseries, a group of plants I’ve mostly been ignoring, so there’s basically no category of plants now that goes uninvestigated. Let me just say that this is an approach that can really blow up a plant budget. Often I find the usual suspects, the spider plants, aglaonemas, spathiphyllums, but occasionally I’m surprised, as I was by this schefflera. Not checking in on houseplants frequently, for all I know it may be commonly available. It’s been a few weeks, but the leaves still retain that incredibly waxy sheen, an effect I assumed was produced by a spray of some sort, and maybe it is. The lemon-lime leaves and red petioles are what turned my head. I haven’t decided yet to keep it or make a present of it for Mother’s Day. It might be best to give it away, because I do seem to be amassing an embarrassing amount of gold-leaved plants.

If I do keep it, here in zone 10 this houseplant is going to be more of a porch plant, where it’s sitting now in almost complete shade until a late afternoon shaft of setting sun grazes it for a short time.

Dappled early morning sun and afternoon shade might be a better choice.

And I don’t see why plants can’t have a bit of styling for their portrait too.

Schefflera actinophylla ‘Soleil’

Marty grabbed these two tall, slim shop chairs from a salvage yard in Gardena for cheap today, as a future sand-and-paint project. In the meantime, I think I’ve found two new plant stands.

The self-guided Mary Lou Heard Memorial Garden Tour stretches from my hometown in Long Beach to about 50 miles south, as far as San Clemete and Mission Viejo. For much too short a span of time, but long enough for so many to become diehard devotees, Mary Lou had the best selection of plants in the South Bay, very much in the style of Annie’s Annuals & Perennials up in Richmond, California, which I think was still wholesale when Mary Lou closed her doors. I was there, along with dozens of other admirers who came to offer our warm thanks that day she closed in 2002, too sick and weak to keep the nursery open any longer, and she died very soon after. Maybe one or two others have tried, but no other local nursery of its kind, with a passion for plants that dared to resist mass-market tastes, has succeeded since the day she locked the gates for the last time.

There were a couple houses on the tour about a mile from me, so those are the ones I chose to attend and drop a stipend in the donation jar for Mary Lou’s favorite charity, The Sheepfold.

Lazy sloth that I am, freeway driving holds no appeal after a busy workweek. But it was well worth attending the two close to home last Saturday, if only to see this vine in full, heat-aroused glory.

The owner didn’t know its name, but it’s got to be Passiflora vitifolia, the Grape-Leaved Passion Fruit.

Also goes by Crimson Passion Flower, and why wouldn’t it?

Buds and bracts were seductively rusty in tone, backed by lush and healthy leaves. It was overall just a stunning vine that the owner admitted was too much for its small trellis to handle. The owner also said never again to opening his garden for a tour. Battling the effects of the heat wave pre-tour had frazzled his nerves. The rest of the garden was in a style that the owner characterized as cottagey, with unhappy roses that had fried in the strong sun, but enormous and healthy, mite-resistant fuchsias for the shadier areas, both some of Mary Lou’s favorite plants, so I know she’d be pleased. And people clamor to have their gardens on this tour, so even if some drop out there are plenty waiting in line. Mary Lou’s legacy tour is still as strong and vibrant as its namesake.

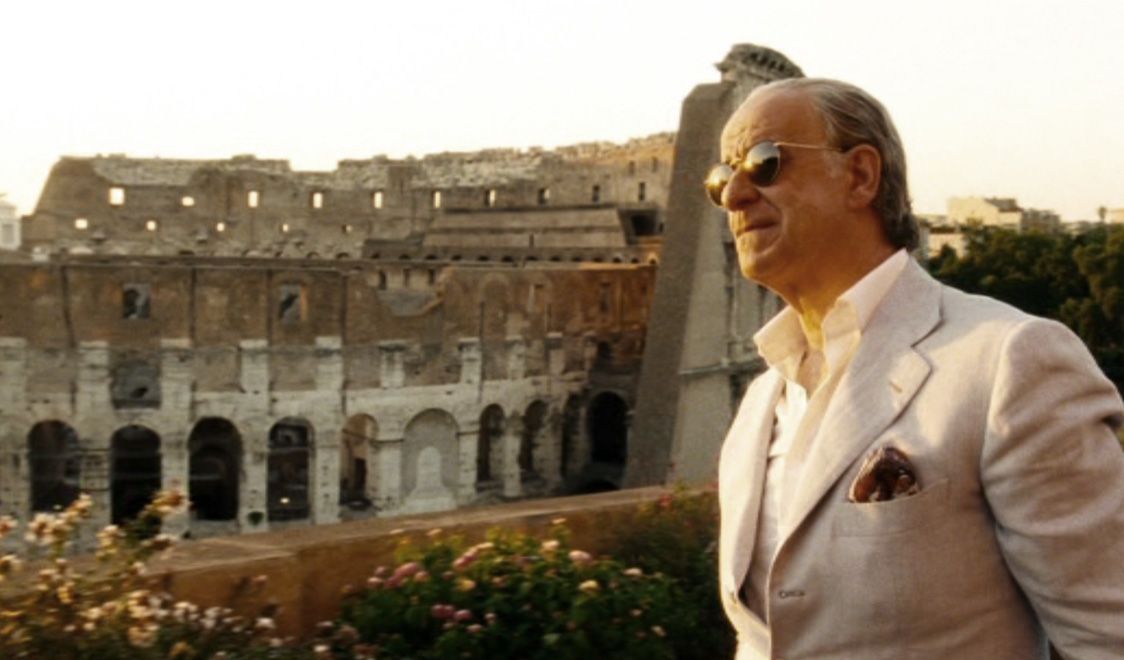

The Great Beauty, awarded the Oscar for best foreign film in 2014, is mysterious and ravishing, like the formal garden Jep’s balcony overlooks, where a nun and children play hide and seek, with the battered hulk of Rome’s Coliseum looming in seemingly touchable proximity. That the Catholic church has played hide and seek with our hero’s search for meaning is another of his disappointments, but the charming journalist Jep Gambardella, a libertine of a man too distracted by the great beauty surrounding him to muster the focus and isolation necessary to complete a followup novel, has nonetheless managed to enjoy himself, perhaps too much. And the garden that his opulent apartment overlooks plays an important, if brief, role in the movie as another of Jep’s exquisite distractions.

Photos found here.

I’ve read some Italian reviews that see the movie as more in the sociopolitical tradition of Visconti’s The Leopard, with The Great Beauty as a commentary on the excesses of Prime Minister’s Silvio Berlusconi’s time in office, though the film maker himself cites Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, also about a distracted journalist, as more of an influence. Like the best movies, this one is roomy enough for multiple interpretations. Although the director Paolo Sorrentino said that he was interested in Rome as a backdrop for the “people who don’t realize that this beauty is all around them,” no doubt alluding to Jep’s charming but neurotically self-absorbed bunch of friends, to me the movie describes the predicament of an artist, one very much inclined to a state of endless intoxication by the spectacular surface of things, and the challenge of sequestering oneself to write novels in a city that is a feast for the senses. Jep yields to the city, to becoming enmeshed in the fascinating intricacies of his friends’ lives and the desperate parties they throw, and now wonders where the time went and why his first love chose someone else. And why he never got around to writing that second book. The long walks Jep takes in the late evening and early morning along the Tiber and through the Eternal City eloquently plead his case that Rome is an artist’s fatal distraction. I’m only half-joking when I say that I think Jep’s temperament is much more suited to landscape design than novels, but as I said, great movies allow for multiple points of view.

Unseasonal, sudden onset heat, like cold, is similarly not in a plant’s best interests. The pristine good looks of Agave ‘Blue Flame’ took a hit last week. Poor thing didn’t have time to develop a base coat and suffered a bad sunburn on a few leaves.

But only a couple feet away, in full sun, delicately pale Agave celsii var. albicans ‘UCB’ absorbed it all in stride.

This New Zealand grass, Harpochloa falx, was planted before the heatocalypse began, possibly the worst conditions imaginable in which to introduce a plant to its new home, yet it seems to have weathered the sunstorm. And if it hasn’t, I’m definitely going back for more. Oddly enough, I’d been chasing down another New Zealand grass, Chionochloa flavicans, which is why I’ve been combing the grass aisles at local nurseries, where this beauty unexpectedly popped up. I finally ordered seed of chionochloa that, knock wood, is germinating nicely. But what a nerve-wracking enterprise seed-sowing can be during a heat wave.

It’s very similar to the Eyebrow Grass, Bouteloua gracilis, which didn’t like my garden one bit and exited roots first fairly quickly.

So excited about this NZ grass, which is evergreen, with a name I might actually remember, reminding me as it does of both Harpo Marx and his brother’s famous eyebrows.

The castor bean plant shot up like Jack’s bean stalk, exulting in a punishing amount of sun.

The bulk of the back garden is made up of tough, rough-and-ready plants that should stand up to whatever the weather has in mind (theoretically). Probably favoring leaves over flowers, it still brings in lots of aerial drama from pollinators. Seen in bloom here is lavender, adored by hummingbirds, bees, butterflies, night moths, all manner of winged creatures, with gaillardia, kangaroo paws, Senecio leucostachys, whose pale yellow flowers naturally age to brown.

Amazing how much hot, dry wind a delicate thing like the annual Orlaya grandiflora can withstand. Its bloom will probably be over by June. Never one to chase the idea of a nonstop, summer-long flowerfest, I’m completely okay with flowers going in and out of bloom. Like savoring seasonal fruit and vegetables, for me it’s the changing rhythms that make a garden that much more exciting.

Some plants had me worried, like burnt ember-colored Isoplexis isabelliana and the digiplexis, all of which did fine. Nothing phases a russelia, yellow flowers on the right. I hand-watered the foxglove relatives all directly at their base, because they definitely showed some heat stress, which I also did for anything newly planted. Everything had already been deeply mulched, which keeps the soil cool.

I wasn’t too sure about spring-planted clary sage either, another plant I hand-watered directly at its base, and so far it seems fine.

I’ve been trying for years to add this sage to my repertoire of self-seeders and feared I’d lost another chance.

This Coprosma ‘Plum Hussy’ was planted last year and didn’t blink in the heat, even though I forgot to give it an extra drink.

Sunday morning brought relatively cooler temps, and having been idled and literally made dizzy by the extreme heat, I was itching to get busy. Half of Eryngium pandanifolium was sprawling onto the terrace off the kitchen, snaking around our feet under the table. I can’t speak for everybody here, but I was prepared to live with these conditions, since I’m thrilled that this fantastic eryngo from South America likes my garden. But now that I’ve got a few seedlings for insurance, I’ll probably remove the main plant and plant something a little less intimidating. Yesterday I cleaned up old leaves and removed three big offsets, which were planted elsewhere, though I doubt they’ll survive. Like all eryngos, they hate root disturbance and are famously touchy about being moved. Worth a try anyway, rather than tossing them in the compost pile. That’s one of the divisions in the photo above with the coprosma.

March 2013, with the eryngo on the left, that surprised me by a) really, really liking my garden, and b) thereby swiftly increasing in size. Agave ‘Blue Flame’ can be seen, too, in better days. The mortared brick path on the right was in place when we bought the house. Instead of bricks and pavers on a bed of sand, I should just gravel in what’s left of the terrace, which is sinking below grade. I keep pulling the bricks out anyway to make room for more plants.

Which is what I did for the eryngo, removing some bricks in secret, of course. Seen here in May 2013, still very puya-esque in character.

Detail of the eryngo’s 6-foot bloom stalk last August.

I’ve just started another promising eryngium from seed, another South American from Argentina, E. bracteatum, which has deep red, bottle brush-type flowers.

Plectranthus neochilus has been stunning this spring, happy with dry soil, overcast skies or extreme heat and strong sunshine. For hazy blue, I should just forego nepeta entirely and go with this plectranthus. The tight, uniform bloom is the stunning result of very harsh treatment. It’s a spreader, so I cut it back hard in winter.

This Echium simplex, growing deep in a border, weathered the heat fine, but another one closer to the bricks suffered leaf burn.

The poppies run to seed fast in extreme heat.

At the front of the house, the jacarandas’ normally sticky blooms had the texture of potato chips underfoot after a few minutes on hot pavement.

Another delicate one that withstood the worst of the heat wave. I will say this about monocarpic plants that die after blooming. They really, really give it their all. It was a pleasure, Melanoselinum decipiens.

If I wake up to a day that has a few extra hours rattling around like loose change in the pockets of Marty’s jeans that I always borrow, clinking against paper clips and last night’s Peroni bottle cap, it’s pretty much guaranteed I’ll make something, not all of which ends up on the blog. Case in point, as Mr. Serling said. There’s this old, topless coffee table base I’ve kept around for just such a day with a few spare hours, which happened to be sometime last summer. Maybe I’d make a new tabletop out of mosaiced bits of salvaged wood lying around. An idea which, big surprise, turned out to involve a basic knowledge of carpentry that I don’t currently possess.

But look, there’s all these succulents that need thinning! You can see where this is headed, in the direction of the craft of least resistance: Succulent table!

Completed in a couple hours, it immediately turned from triumph into garden albatross, taking up all the room of a coffee table with zero functionality. In my zeal to make use of excess succulent cuttings, I neglected to build into it a flat surface, even if only large enough for a cup of coffee. Or a Peroni.

At the end of some ill-fated projects, there’s that weird sensation, a mixture of both accomplishment and dread. This was one of those projects.

But the succulents were thriving in the shallow, free-draining root run, a hammock of hardware cloth mossed to hold soil, so I continued to care for it, cursing freely when my knees banged into the table, as they often did. With summer approaching, and chairs and tables getting shuffled, I really wanted it out of the way, preferably in a spot shielded from full sun to reduce watering needs. And if there wasn’t a suitable spot, it was time for the albatross to go.

Looking around this tiny garden for a scrap of space I’ve somehow overlooked, as I’ve done a zillion times before, I settled on a gap between the Monterey cypresses against the eastern fence. Not wanting to crowd these important privacy screens, I’d left the ground mostly bare among the three. The table tucked in snugly between two, and the albatross was, at last, no longer underfoot. In fact, the albatross loved its new protected location so much that the succulents plumped up and spilled over the sides, hiding the armature of hardware cloth. And for the first time it didn’t seem quite so silly after all.

Tucked in against the fence, even this week’s hot and fiercely dry Santa Ana winds couldn’t touch it. Now, instead of a failed table, it’s an abstract band of mostly bright Aeonium ‘Kiwi’ floating about 3 feet above ground level, lighting up the gloom at the base of the cypresses.

(Here’s a closeup of the fasciation on that bloom of Euphorbia lambii you probably noticed.)

Once the cypresses and a couple shrubs mature/survive, the albatross will have to be relocated, but it can stay through summer.

Just forward of the cypresses, the shrubs are dark-leaved Ceanothus ‘Tuxedo’ in the foreground and Leucospermum ‘Sunrise’ in the distance.

Now the succulent table experiment has me thinking in new directions. After visiting the Moorten Botanical Garden, building raised benches for succulents and cacti has become an intriguing possibility I’ve been keeping open for an underused side patio, something I can practice on with those basic carpentry skills I hope to acquire.

There’s no telling which of these, if either, will be around for photos next year, so now’s the time for a side-by-side color comparison.

According to this article, it was Isoplexis canariensis that was crossed with Digitalis purpurea to give us Digiplexis ‘Illumination Flame.’ The bottom photo is of Isoplexis isabelliana, but the color if not the flower shape is a good semblance of I. canariensis, with probably less gold and more burnt orange. (Being ever on the lookout for the tall, spiky, and orange, I’ve trialed a few isoplexis. I. canariensis was short-lived in my garden.) The shocking pink, apricot-throated digiplexis to my eye exudes a Jonathan Adler-inspired play with colors. In its new guise, dear old digitalis has been liberated from the genteel confines of the shady cottage garden. Even though able to handle full sun, especially near the coast, the unseasonal 20-degree jump into the 90s today and for the rest of the week is not to either plant’s liking, or mine for that matter. I’ve had verbascums collapse under similar conditions. They both held up surprisingly well this first day of the heat wave. Some lateral spikes broke off a few days ago but were saved for a vase.

Digiplexis ‘Illumination Flame’

Isoplexis isabelliana

If it lives up to its sturdy reputation, I wouldn’t be surprised if digiplexis has a future as a florist’s pet.