With this July being the 50th anniversary of the moon landing, it’s been nonstop space coverage here at home. I doze off and on, but Marty is absolutely rapt, so I can always quiz him afterwards on what I missed.

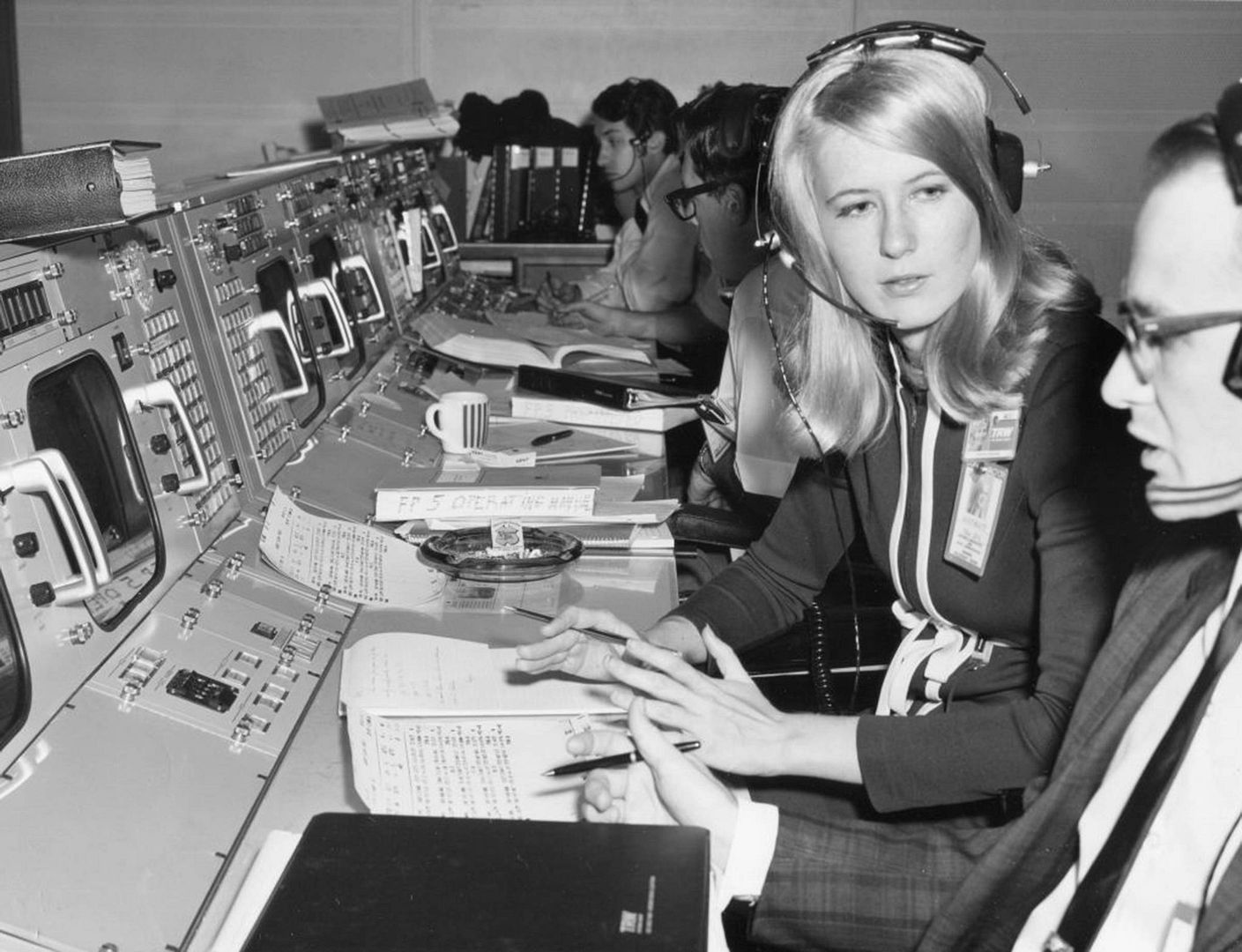

(engineers come in all shapes — do you think there was any mansplaining going on at mission control?)

I was awake, though, to learn about Poppy Northcutt, the first female engineer in mission control, who was hired as a “computress” — where’s the movie on Poppy? It’s such an enthralling story. And she bears a remarkable resemblance to Kirsten Dunst, so the casting practically takes care of itself.

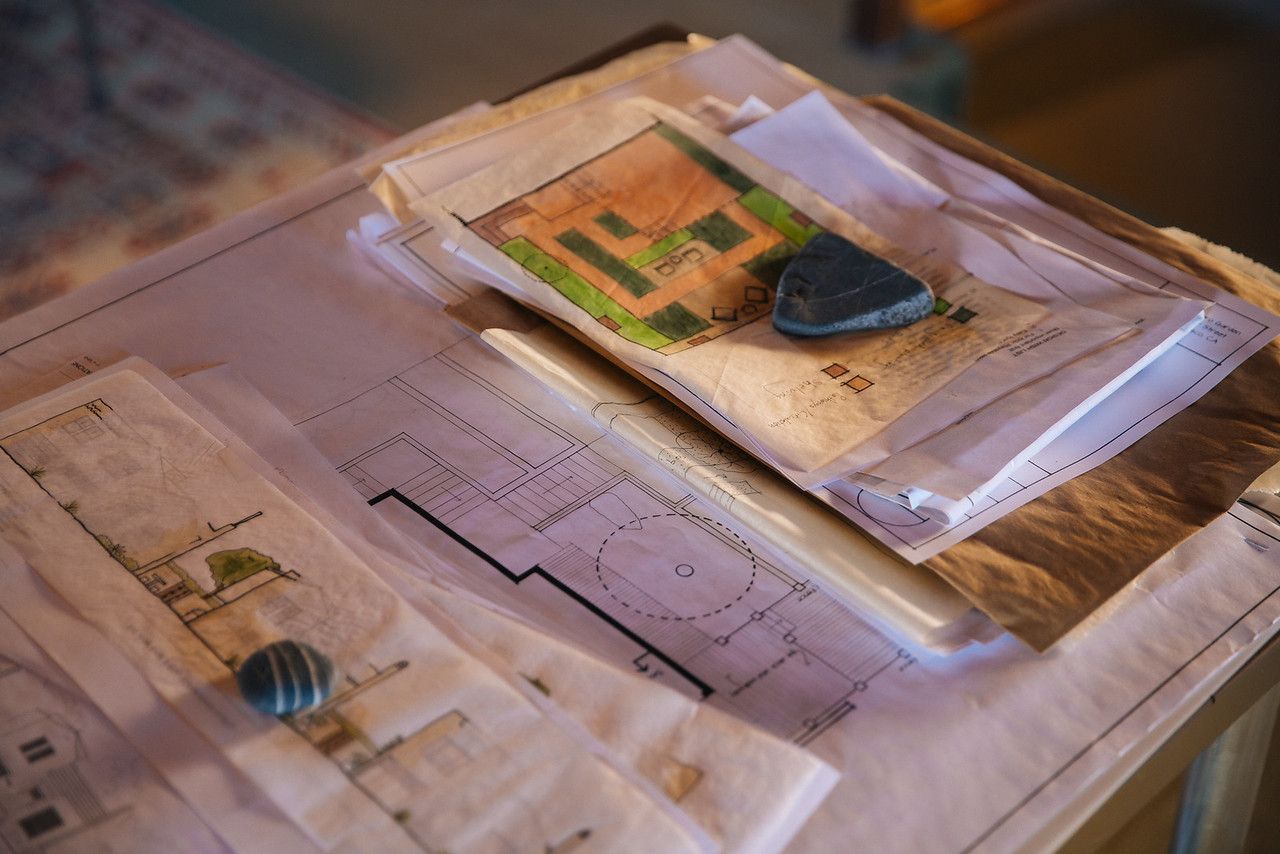

photo by MB Maher

The shapes that inspire artists, engineers and designers are all around, and I can’t wait to learn more of the back story behind Josh Rosen’s latest creation pictured above and below.

The airplantman has devised a new structure/habitat that maximizes the conditions for tillandsias to flourish — in a celestial shape that the eye just doesn’t want to let go. Hopefully we’ll all know more in the next few weeks.

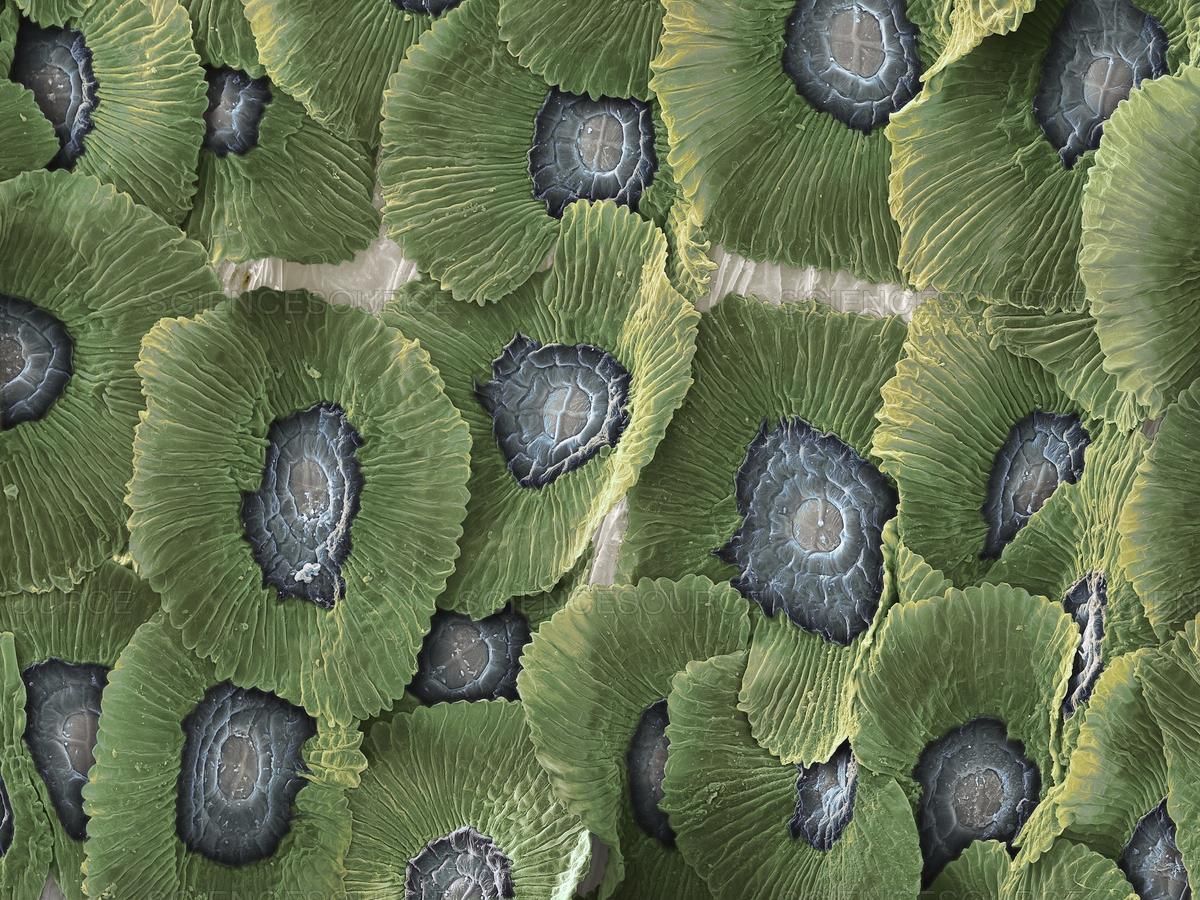

via Science Source

More mesmerizing shapes. This silo belongs to the Denver Botanic Garden’s Chatfield Farms. We just got back from a road trip up the California coast into Oregon, where silos, barns, and granaries gracefully dot smallish farms with their intensely green geometric grids of summer vegetables. Whether in space or here on Earth, there’s so many inspiring shapes all around, whether purpose-built by natural selection or by us for our various schemes. I’m a city kid, born and raised, which might be why farm buildings exert such a powerful pull on my urban imagination. Buildings crafted to facilitate specific tasks are so incredibly stripped down and pure. Very reminiscent of the adaptations of plants in a way.

Here in Los Angeles, the local gas refineries, with their low tanks and slim minarets lit up and sparkling at night, were exotic, glittering cities before I knew any context for their real purpose. Incredibly, the Saturn 5 rocket that took us to the moon burned more fuel in 1 second than Lindberg’s trip across the Atlantic. Ask Marty, he’ll tell you all about it. My next question to him will be: Can we get the manned mission to Mars off the ground with biofuel?

Have a great weekend.