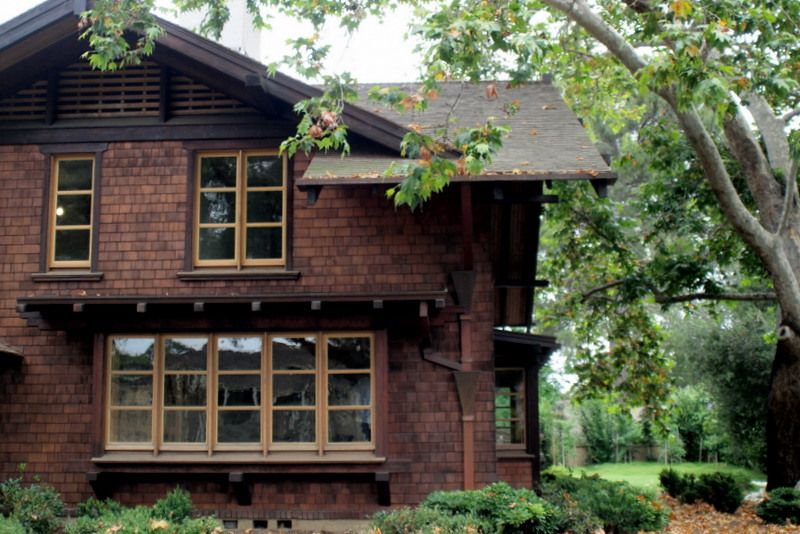

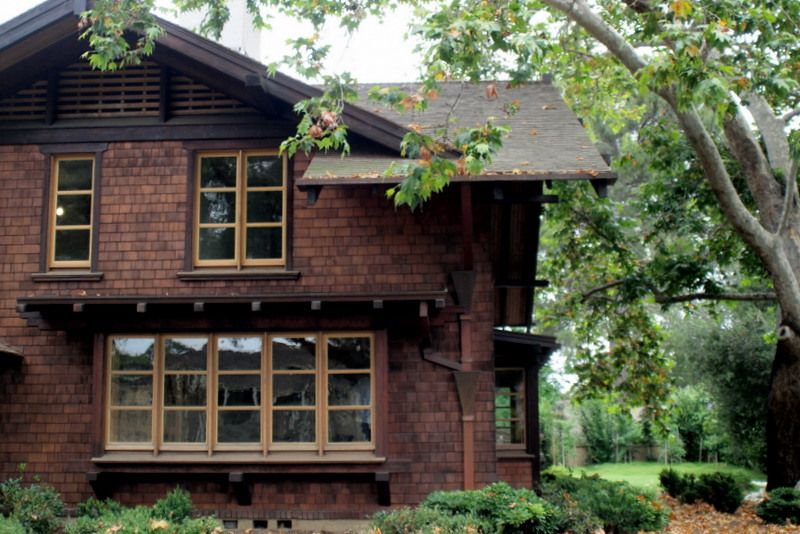

There was a small tour of five local historical homes on Sunday presented by Long Beach Heritage. The star of the tour from a rarity perspective was this Greene & Greene, one of only three here in Long Beach. Even on such a small tour, I only managed to see three of the five houses. Must build up some tour discipline! It’s just that these old houses and gardens have so very many stories to tell…

Some houses in my neighborhood contributed panes of the old “wavy” glass for the restoration of this “National Historic landmark…this 1904 house survived by moving three times. Designed by the Greenes as an oceanfront home for Jennie A. Reeve…the house is one of the brothers’ earliest ventures in Arts and Crafts style. Moved to its current location in 1924…Henry Greene was rehired to design a significant two-story addition and garden. The house is currently under restoration.”

I’ll say it’s under restoration. History-making, monumental, meticulous restoration undertaken by the current owner, a restoration architect, using the original Greene & Greene plans, which include not only plans for the built-ins, but the furniture, fixtures and landscape as well. There are only a few of the original decorative items and light fixtures left. The original porch light is temporarily on loan to the Huntington while the house is restored. All other decorative fixtures, and there were over 100, have long since disappeared during the house’s various moves — no one seems to know how or to whom, but someone was made very rich by the pillaging. The floors are quarter-sawn oak, the built-in cabinetry and mouldings Port Orford cedar, which due to its rarity arrives in well-spaced, restoration-prolonging shipments. With restoration still underway, the Reeve house was completely empty, lath and plaster still exposed in some rooms, which provided a fascinating look at the painstaking process of restoration. Completion of the house is estimated for the end of this year, but there’s still the furniture, fixtures and landscape to be finished.

No interior photos were allowed in any of the homes, only the exterior. I was excited that a couple homes on the tour were reputed to have extensive gardens.

This enormous garden belonged to a home on the tour that sat on three lots, but its allure now is mostly its ghostly state of disrepair. There were mature fruit trees, overgrown roses, daylilies, agapanthus, the garden seen through this glassed-in outdoor patio draped in jasmine.

At one time in its past, an oil derrick was moved onto the property and pumped for one day. The docent kept repeating this story with no other explanation. Why just one day? Was it removed because of the nuisance factor, or could they tell the well was dry after one day? Many of the homes here still sell with their mineral rights.

Other survivors were ropes of epiphytic cactus.

And a collection of succulents on the back steps

The kitchen garden was still in active use.

A Spanish Revival home on the tour had a sweet courtyard, viewed here from a secret garden

The courtyard opened off the back door and also led through a doorway to the front of the property

Along with an armoire for storage, there was a massive brick fireplace, a small fountain, low-light plants like the fiddle-leaf fig and staghorn fern.

the arched doorway leading to an inner graveled garden

the secret garden

Just outside the walled courtyard on the path to the street, a chair is nearly hidden by bougainvillea. The swath of green on the left is Salvia spathacea, so it’s obviously a hummingbird-viewing station, right?

Before heading home, a quick stop for a nearby parkway abloom in Salvia clevelandii and Salvia canariensis.

Salvia canariensis is one of my favorite salvias and ruled the garden last summer. This parkway was double-wide, so it had all the space it needed. With lavender, artemisia, stachys, nepeta

A lush gift for insects, birds and the neighborhood to enjoy…and the occasional itinerant tour-goer.