“None of the ants previously seen by man were more than an inch in length – most considerably under that size. But even the most minute of them have an instinct and talent for industry, social organization, and savagery that makes man look feeble by comparison.” — Them! (1954 movie on gigantic, killer, atomic-radiated ants)

End of month view down the pergola looking east.

Possibly the best thing about my summer garden 2015 is Eucalyptus ‘Moon Lagoon’

In late summer it’s putting out this chartreuse, willowy new growth, which is mesmerizing against the backdrop of its own tangled-up-in-blue leaves. (Speaking of color, where’s your famous fiery red response to strong sun, Aloe cameronii? Not hot enough for you? It’s been plenty hot for me, thanks.)

A very telescoped view from the west gate to show the wash of blue that’s taken over the garden. ‘Moon Lagoon’ in the foreground, Acacia baileyana ‘Purpurea’ in the background (and blue apartment building in the distance). Just looking at the froth of blue cools me down.

The three that I was possibly most anxious to see make it through summer are just outside the office. Columnar Cussonia gamtoosensis is almost fence height now. The Coast Woolybush to the right, Adenanthos sericeus, has been a peach all summer.*

And Grevillea ‘Moonlight’ seems safely established here too.

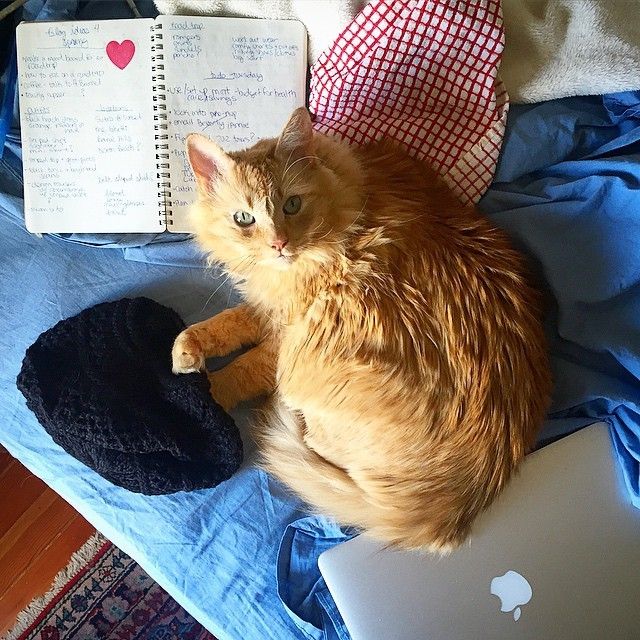

Impromptu birdbath, which looks an awful lot like a headstone monument to a fallen aloe.

That’s an abbreviated EOMV so we can get to the bug report. Possibly the worst thing about my summer garden 2015 has been the ants. Apparently, if Southern California had a resident population of feisty fire ants, we wouldn’t be experiencing a scourge of Argentine ants, but we don’t, so we are. Linepithema humile stowed away on ships bound for our ports sometime in the 1980s, and life just hasn’t been the same since. Native ants were pushovers, no contest at all. I don’t like to dwell on this fact for long or I’d probably run away from home, but scientists tell us that the Argentine ants all belong to one giant SUPER COLONY. Which in practical terms means, because they’re all bros, they don’t fight. They amiably cooperate in a tireless, jack-booted bid for world domination. They are the Uruk-hai of ants. They seek out the same conditions we do, not too hot or cold, not too wet or dry, just nicely warmish and humid.

So when it’s too dry they line up around the shower with their tiny towels, circle the sinks with itty-bitty tooth brushes. They’re everywhere. Them!

I put together this little birdbath to take the place of an Aloe capitata that fell victim to the ants. All summer our insect overlords have relegated us to squatter status on our own property. This summer it seems like they’ve really stepped up their association (“mutualism”) with their nasty symbiotic playmates, scale insects and mealybugs. Ants offer safe transit and escort the pests into the crevices and crowns of some plants. Not all, just mostly my favorites, it seems. The stemless aloes have been hit hard this summer. A perky Aloe capitata var. quartzicola went flaccid seemingly overnight. Upon investigation, the lower crown was stuffed with scale. Them! For weeks I enraged the ants by scraping off scale from the aloe’s leaves, pouring cinnamon onto the crown, digging in coffee around the base. The ants supposedly hate strong smells. The aloe seemed to partially recover but lost so many leaves that I dug it up to nurse along in a pot. Aloe cryptoflora has also succumbed, and a large fan aloe was weakened and killed by ants, though it wasn’t in great shape when I bought it.

Aloe ‘Rooikappie’ is now taking its chances after A. capitata var. quartzicola was dragged off the battlefield.

Aloe capitata var. quartzicola in better days. If I find one again it will live in a container.

The ants favorite victims are stemless aloes planted close to hardscape, but they also favor beschornerias. The hardscape of bricks laid dry, without mortar, on a layer of sand has provided perfect Ant Farm conditions. Agave ‘Cornelius’ seems impervious so far, but ants are herding scale on some agaves like the desmettianas.

Beschorneria ‘Flamingo Glow’ has had its lower leaves stripped away frequently due to infestations. B. albiflora is under attack too.

This former wine stopper holding the birdbath together sums it up: we’re barely treading water against the ants. A vinegar spray solution stops attacks indoors, and cinnamon spread on window sills has been an effective barrier. (The glass shade was in the house when we bought it, and the concrete base was part of the chimney flue.)

I can’t remember ever having mealybug problems with agaves. I’ve been frequently knocking them off ‘Dragon Toes.’

Agave vilmoriniana ‘Stained Glass’ still seems clean.

Since the yucca has bloomed and become multi-headed, it seems to be attracting ants and scale too.

The furcraea is clean and has mostly outgrown damage from hail earlier in the year.

Aloe elgonica still looks clean from scale.

Potted plants have to be watched too. This boophane is clean, but pots of cyrtanthus are targets for scale.

I admit to indulging in some self-pity shopping. I’ve been wanting to try Artemisia ‘David’s Choice.’ The ants helped clear the perfect spot to try three.

Euphorbia ‘Lime Wall.’ I’ve yet to have scale on euphorbias, but you never know.

No more talk of bugs. Xanthosoma ‘Lime Zinger’ loves August, so I love xanthosoma.

I was this close to composting these begonias but gave them a reprieve, daring them to grow in a very shallow container. I thought I wanted some hot color in August, but turns out, nope, not really. I had a bunch of rooted cuttings of Senecio medley-woodii which grow lanky in very little soil, so stuck them in with some rhipsalis to chill this begonia the hell out.

Happy plants grouped under the light shade of the fringe tree on the east side of the house.

This succulent is very confusing. With alba in the name, I’m thinking white flowers. No, Crassula alba var. parvisepala reportedly has stunning trusses of deep red flowers. This is mine in bloom. I guess we’re both confused.

I have to say that there’s been a splendid show of butterflies all summer. The June bugs fizzled out, which is fine by me. (So weird that image searches of the June bug bring up what I know as the fig beetle. My June bug is, I think, Phyllophaga crinita.) It’s also been a banner year for the flying fig beetles, Cotinis mutabilis. The grasshoppers surprisingly haven’t been too bad.

End of month views are collected by The Patient Gardener, with or without bug reports.

*But was dead when I returned after a week’s absence, the soil bone-dry. Another has already been installed elsewhere in the garden.